Difference between revisions of "Pensacola streetcar system"

(add image) |

|||

| (34 intermediate revisions by 7 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

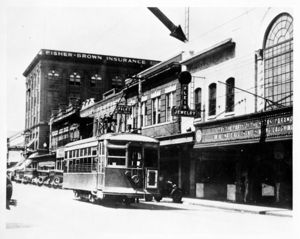

[[Image:PensacolaTrolley.jpg|thumb|A trolley travels south on [[Palafox Street]], circa 1920s]] | [[Image:PensacolaTrolley.jpg|thumb|A trolley travels south on [[Palafox Street]], circa 1920s]] | ||

| − | The '''Pensacola streetcar (trolley) system''' was operated by the [[Pensacola Electric Company]] in [[ | + | The '''Pensacola streetcar (trolley) system''' was a public transportation system that was operated by various entities between [[1884]] and [[1932]]. |

| + | |||

| + | ==History== | ||

| + | ===Origins=== | ||

| + | The streetcar system in Pensacola can be traced to [[Conrad Kupfrian]], a German immigrant who was reportedly inspired by the horsecars he saw in St. Louis on a business trip. He formed a partnership, the [[Pensacola Streetcar Company]], with [[Henry Pfeiffer]] and [[John Cosgrove]]. The men raised $50,000 in capital for the project and, on [[November 15]], [[1882]], convinced the [[Pensacola City Council]] to pass an ordinance allowing steel track to be placed in the roadways. The first streetcars, which went operational in [[1884]], ran from [[Pensacola Bay]] north along [[Palafox Street]] to [[Wright Street]], then east to the [[Union Depot]], then south along [[Alcaniz Street|Alcaniz]] to [[Gregory Street|Gregory]] and west to [[DeVilliers Street]]. A north-south link at DeVilliers went south to [[Government Street]] and east again to Palafox. A general fare cost five cents, and cars passed about every ten minutes during high-traffic periods. The company addressed the issue of low ridership after business hours by creating an amusement park destination, called [[Kupfrian's Park]], in the [[North Hill]] neighborhood, extending the line west from DeVilliers on [[La Rua Street|La Rua]] and north on [[J Street]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===First reorganization=== | ||

| + | Between [[1890]] and [[1891]], the Pensacola Streetcar Company was reorganized as the [[Pensacola Terminal Company]] under directors [[J. H. Carter]], [[J. M. Carter]] and [[Thomas C. Watson]]. They created a new line, called the Dummy Line for its use of [[Wikipedia:steam dummy|steam dummy]] engines, that stretched along [[Bayshore Drive]] to [[Warrington]] and [[Woolsey]], allowing [[Navy Yard]] employees a convenient means to reach the city core. The lines were also extended north to [[Blount Street]] and east to [[East Pensacola Heights]]. The cost of the extension, which included bridges over [[Bayou Chico]] and [[Bayou Texar]], was paid by selling revenue bonds. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Second reorganization=== | ||

| + | An economic downturn affected the streetcar company in [[1897]]. It was reorganized again as the [[Pensacola Electric Terminal Railway Company]], with Captain [[William H. Northrup]] as president. [[William A. Blount]]'s law firm assisted in the transition and introduced northern firm Stone & Webster to help develop the utility. The [[Pensacola Electric Light & Power Company]] was also incorporated in [[1897]], building a coal-powered generator at [[Baylen Street|Baylen]] and [[Cedar Street]]s that provided power to much of the area. Elevated wires were placed over the streets to provide electricity to the trolleys; a double set of tracks were placed in the broad [[Palafox Street]]; and a streetcar barn and mechanical shop was built at [[Gadsden Street|Gadsden]] and [[DeVillier Street]]s. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Stone & Webster ownership=== | ||

| + | In June [[1906]], Boston conglomerate [[Wikipedia:Stone & Webster|Stone & Webster]] took over the city's streetcar and electric systems. A 1908 issue of the ''Stone & Webster Public Service Journal'' describes the improvements Stone & Webster made to the system, as well as its operations in 1908: | ||

| + | <blockquote>It was in 1906 that the Stone & Webster organization took charge of the traction and electric lighting systems of Pensacola, both of which it has improved. At that time there was a line seven and one-half miles along the shore to Fort Barancas (sic) — is, to the government reservation, where the navy yard is located, and where a good-sized colony exists. This line was electrified for only about a third of the distance, steam being employed over the balance. Today, electricity is the sole power. The city lines of the old company were in inadequate condition, but the situation in this respect has since been much improved. All told, the street railway company now operates 20.39 miles of track. Its equipment consists of 26 passenger cars, with 9 trailers, together with one express car and 11 miscellaneous cars. Power for both the street railway and lighting is supplied from a brick power station, with a capacity for 700 Kw. for lighting and 800 Kw. for traction purposes. The equipment includes a new 300 Kw. Parson's steam turbine, and a new direct connected 500 Kw. railway generator. A brick repair shop, a car barn and several parcels of land in the city are owned by the company. The distributing system of the lighting plant is in excellent condition, having recently been overhauled and thoroughly rebuilt. The electric light franchise is perpetual, having been granted by special act of the legislature. The railway franchise expires in 1933. That part of the line running to the government military reservation is operated under authority granted by the Secretary of War, the grant on the naval reservation being by special act of Congress.</blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

| + | From [[April 5]]-[[May 13]], [[1908]], the Pensacola Electric Company's unionized workers staged a [[Streetcar operators' strike|strike]]. The highly contentious strike led to numerous incidents of violence, requiring the Florida state militia to be sent to Pensacola to maintain peace. | ||

| + | |||

| + | On [[May 19]], 1908, shortly after the strike's end, two streetcars from the Park and Belt lines collided, killing one woman and injuring another.<ref>The ''Montgomery Advertiser'', May 20, 1908. [http://www3.gendisasters.com/florida/8925/pensacola-fl-street-car-wreck-may-1908]</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Demise of the streetcar system== | ||

| + | In 1928 the [[St. Louis-San Francisco Railway]] bought the old dummy line for freight purposes; a bit of trackage still exists on the south side of Main Street between Clubbs and A, where the line curved southwest toward Pine. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In [[1929]], the City passed an ordinance authorizing Gulf Power to discontinue service and remove trackage for the portion of the system servicing the [[Hawkshaw]] area.<ref>Ordinance No. 7, Series No. 19, City of Pensacola. [[August 5]], [[1929]].</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The City authorized Gulf Power to surrender its streetcar franchise in November [[1931]], "in consideration" of an $18,000 credit to be applied towards the City's debt to Gulf Power.<ref>Ordinance No. 10, Series No. 1, City of Pensacola. [[November 30]], [[1931]].</ref> After adoption of the ordinance terminating the franchise, Gulf Power agreed to reduce the interest rate on the City's debt from eight to six percent per year.<ref>Contract between Gulf Power and the City of Pensacola dated December 31, 1931.</ref> Streetcar service was discontinued in [[1932]], replaced by motor bus service operated by the [[Pensacola Coach Corporation]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | At its peak, a total of 30 trolley cars carried four million passengers per year (1920).<ref>[http://www.dot.state.fl.us/publicinformationoffice/historicdotphotos/rail/pentrolley.htm MyFlorida.com]</ref> Partially covered tracks and barely concealed right-of way are clearly visible in various places along the former routes, including on West [[Gadsden Street]], West [[DeSoto Street]],<ref>[http://maps.google.com/?ie=UTF8&ll=30.422958,-87.220094&spn=0.01286,0.019312&z=16&layer=c&cbll=30.422841,-87.219968&panoid=DKB9xa_j9I6kFEHTAn8nmg&cbp=12,259.17608183457696,,0,14.54100241579118 Google Maps Street View]</ref> and East [[Jackson Street]].<ref>[http://maps.google.com/?ie=UTF8&ll=30.418702,-87.209151&spn=0.01286,0.019312&z=16&layer=c&cbll=30.422921,-87.196446&panoid=ynzkZ_-A2Lj1l73a8mwYUw&cbp=12,76.9141215041957,,0,3.1568518060403385 Google Maps Street View]</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Segregation== | ||

| + | [[Segregation]] of the streetcar system came in [[1905]] via a state law authored by Pensacola representative [[John Campbell Avery]]. Soon after the law was approved by the Florida Legislature, Pensacola's African-American community initiated a boycott of the streetcar system. The streetcar system's management reported on the boycott to the Stone & Webster corporate office: | ||

| + | {{cquote|In Pensacola 90% of the negroes have stopped riding even though the company has not issued an order or intimated anything as to what they intend to do. The negroes have appointed Committees who meet negroes visiting their city at the train and present each one with a button to be worn in the lapel of the coat. This button bears the single word WALK.|20px|20px|Letter of John E. Hartridge to William H. Tucker, May 28, 1905.<ref>Ortiz, Paul. ''Emancipation Betrayed''. University of California Press, 2005.</ref>}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | However, the Avery law was declared unconstitutional by the Florida Supreme Court a month later. The [[Pensacola City Council]] responded with an ordinance that was | ||

| + | <blockquote>somewhat similar to the state law which was declared unconstitutional. It was drawn however, in such shape that it will hardly be declared unconstitutional if any attempt is made to carry it to the Supreme Court. The street railway company will divide the cars as it did during the time that the state law was being complied with, except that cards will be posted designaling the white and colored parts of a car. The colored population seems to be satisfied and it is not expected that the cars will be boycotted as was the case when the state law [became] operative.<ref>"Jim Crow Law Effective To-Day." ''Pensacola Journal'', October 13, 1905.</ref></blockquote> | ||

| + | Despite being vetoed by [[Pensacola Mayor|Mayor]] [[Charles H. Bliss]], the ordinance was passed by the council and went into effect on [[October 13]], 1905. | ||

| + | {{sectstub}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Streetcar lines== | ||

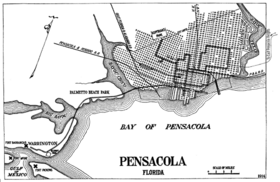

| + | [[Image:Streetcar-map.PNG|thumb|right|280px|1914 map of the streetcar system]] | ||

| + | ===East Hill Line=== | ||

| + | The '''East Hill''' line ran in somewhat of a loop, going up [[Alcaniz Street]] from [[Gregory Street|Gregory]] to [[Brainerd Street]]s, then east on Brainerd to [[6th Avenue]], north on 6th Avenue to [[Blount Street]], east on Blount to [[16th Avenue]], south on 16th to [[Jackson Street]], then west on Jackson to [[8th Avenue]], then south on 8th to [[Wright Street]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===North Hill Line=== | ||

| + | ===Belt Line=== | ||

| + | ===West Hill (or Park) Line=== | ||

| + | The '''West Hill''' or '''Park Link''' headed west on [[la Rua Street]] from [[de Villiers Street]], turning north on [[J Street]] and terminating at [[Kupfrian's Park]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Navy Yard (or Barrancas) Line=== | ||

==Other images== | ==Other images== | ||

| − | <gallery> | + | <gallery perrow="4"> |

Image:Car35.jpg|Conductors by street car number 35, early 1900s | Image:Car35.jpg|Conductors by street car number 35, early 1900s | ||

Image:SPalafox-streetcars.jpg|South [[Palafox Street]], early 1900s | Image:SPalafox-streetcars.jpg|South [[Palafox Street]], early 1900s | ||

Image:PalafoxStreetcars.jpg|South Palafox Street, date unknown | Image:PalafoxStreetcars.jpg|South Palafox Street, date unknown | ||

| + | Image:BayshoreCar.jpg|Bayshore line car, circa [[1930]] | ||

| + | Image:Car13.jpg|Car 13, date unknown. | ||

| + | Image:Streetcar-PFVII.jpg|South [[Palafox Street]] near [[Plaza Ferdinand VII]] | ||

| + | Image:BayshoreCar9.jpg|Unidentified woman on Bayshore car number 9 | ||

| + | Image:Carbarn.PNG|The streetcar barn, [[1908]] | ||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | + | {{reflist}} | |

| − | + | [[Category:Public transportation]] | |

Latest revision as of 18:47, 19 March 2018

The Pensacola streetcar (trolley) system was a public transportation system that was operated by various entities between 1884 and 1932.

Contents

History[edit]

Origins[edit]

The streetcar system in Pensacola can be traced to Conrad Kupfrian, a German immigrant who was reportedly inspired by the horsecars he saw in St. Louis on a business trip. He formed a partnership, the Pensacola Streetcar Company, with Henry Pfeiffer and John Cosgrove. The men raised $50,000 in capital for the project and, on November 15, 1882, convinced the Pensacola City Council to pass an ordinance allowing steel track to be placed in the roadways. The first streetcars, which went operational in 1884, ran from Pensacola Bay north along Palafox Street to Wright Street, then east to the Union Depot, then south along Alcaniz to Gregory and west to DeVilliers Street. A north-south link at DeVilliers went south to Government Street and east again to Palafox. A general fare cost five cents, and cars passed about every ten minutes during high-traffic periods. The company addressed the issue of low ridership after business hours by creating an amusement park destination, called Kupfrian's Park, in the North Hill neighborhood, extending the line west from DeVilliers on La Rua and north on J Street.

First reorganization[edit]

Between 1890 and 1891, the Pensacola Streetcar Company was reorganized as the Pensacola Terminal Company under directors J. H. Carter, J. M. Carter and Thomas C. Watson. They created a new line, called the Dummy Line for its use of steam dummy engines, that stretched along Bayshore Drive to Warrington and Woolsey, allowing Navy Yard employees a convenient means to reach the city core. The lines were also extended north to Blount Street and east to East Pensacola Heights. The cost of the extension, which included bridges over Bayou Chico and Bayou Texar, was paid by selling revenue bonds.

Second reorganization[edit]

An economic downturn affected the streetcar company in 1897. It was reorganized again as the Pensacola Electric Terminal Railway Company, with Captain William H. Northrup as president. William A. Blount's law firm assisted in the transition and introduced northern firm Stone & Webster to help develop the utility. The Pensacola Electric Light & Power Company was also incorporated in 1897, building a coal-powered generator at Baylen and Cedar Streets that provided power to much of the area. Elevated wires were placed over the streets to provide electricity to the trolleys; a double set of tracks were placed in the broad Palafox Street; and a streetcar barn and mechanical shop was built at Gadsden and DeVillier Streets.

Stone & Webster ownership[edit]

In June 1906, Boston conglomerate Stone & Webster took over the city's streetcar and electric systems. A 1908 issue of the Stone & Webster Public Service Journal describes the improvements Stone & Webster made to the system, as well as its operations in 1908:

It was in 1906 that the Stone & Webster organization took charge of the traction and electric lighting systems of Pensacola, both of which it has improved. At that time there was a line seven and one-half miles along the shore to Fort Barancas (sic) — is, to the government reservation, where the navy yard is located, and where a good-sized colony exists. This line was electrified for only about a third of the distance, steam being employed over the balance. Today, electricity is the sole power. The city lines of the old company were in inadequate condition, but the situation in this respect has since been much improved. All told, the street railway company now operates 20.39 miles of track. Its equipment consists of 26 passenger cars, with 9 trailers, together with one express car and 11 miscellaneous cars. Power for both the street railway and lighting is supplied from a brick power station, with a capacity for 700 Kw. for lighting and 800 Kw. for traction purposes. The equipment includes a new 300 Kw. Parson's steam turbine, and a new direct connected 500 Kw. railway generator. A brick repair shop, a car barn and several parcels of land in the city are owned by the company. The distributing system of the lighting plant is in excellent condition, having recently been overhauled and thoroughly rebuilt. The electric light franchise is perpetual, having been granted by special act of the legislature. The railway franchise expires in 1933. That part of the line running to the government military reservation is operated under authority granted by the Secretary of War, the grant on the naval reservation being by special act of Congress.

From April 5-May 13, 1908, the Pensacola Electric Company's unionized workers staged a strike. The highly contentious strike led to numerous incidents of violence, requiring the Florida state militia to be sent to Pensacola to maintain peace.

On May 19, 1908, shortly after the strike's end, two streetcars from the Park and Belt lines collided, killing one woman and injuring another.[1]

Demise of the streetcar system[edit]

In 1928 the St. Louis-San Francisco Railway bought the old dummy line for freight purposes; a bit of trackage still exists on the south side of Main Street between Clubbs and A, where the line curved southwest toward Pine.

In 1929, the City passed an ordinance authorizing Gulf Power to discontinue service and remove trackage for the portion of the system servicing the Hawkshaw area.[2]

The City authorized Gulf Power to surrender its streetcar franchise in November 1931, "in consideration" of an $18,000 credit to be applied towards the City's debt to Gulf Power.[3] After adoption of the ordinance terminating the franchise, Gulf Power agreed to reduce the interest rate on the City's debt from eight to six percent per year.[4] Streetcar service was discontinued in 1932, replaced by motor bus service operated by the Pensacola Coach Corporation.

At its peak, a total of 30 trolley cars carried four million passengers per year (1920).[5] Partially covered tracks and barely concealed right-of way are clearly visible in various places along the former routes, including on West Gadsden Street, West DeSoto Street,[6] and East Jackson Street.[7]

Segregation[edit]

Segregation of the streetcar system came in 1905 via a state law authored by Pensacola representative John Campbell Avery. Soon after the law was approved by the Florida Legislature, Pensacola's African-American community initiated a boycott of the streetcar system. The streetcar system's management reported on the boycott to the Stone & Webster corporate office:

| In Pensacola 90% of the negroes have stopped riding even though the company has not issued an order or intimated anything as to what they intend to do. The negroes have appointed Committees who meet negroes visiting their city at the train and present each one with a button to be worn in the lapel of the coat. This button bears the single word WALK. | ||

—Letter of John E. Hartridge to William H. Tucker, May 28, 1905.[8] | ||

However, the Avery law was declared unconstitutional by the Florida Supreme Court a month later. The Pensacola City Council responded with an ordinance that was

somewhat similar to the state law which was declared unconstitutional. It was drawn however, in such shape that it will hardly be declared unconstitutional if any attempt is made to carry it to the Supreme Court. The street railway company will divide the cars as it did during the time that the state law was being complied with, except that cards will be posted designaling the white and colored parts of a car. The colored population seems to be satisfied and it is not expected that the cars will be boycotted as was the case when the state law [became] operative.[9]

Despite being vetoed by Mayor Charles H. Bliss, the ordinance was passed by the council and went into effect on October 13, 1905.

Streetcar lines[edit]

East Hill Line[edit]

The East Hill line ran in somewhat of a loop, going up Alcaniz Street from Gregory to Brainerd Streets, then east on Brainerd to 6th Avenue, north on 6th Avenue to Blount Street, east on Blount to 16th Avenue, south on 16th to Jackson Street, then west on Jackson to 8th Avenue, then south on 8th to Wright Street.

North Hill Line[edit]

Belt Line[edit]

West Hill (or Park) Line[edit]

The West Hill or Park Link headed west on la Rua Street from de Villiers Street, turning north on J Street and terminating at Kupfrian's Park.

[edit]

Other images[edit]

South Palafox Street, early 1900s

Bayshore line car, circa 1930

South Palafox Street near Plaza Ferdinand VII

The streetcar barn, 1908

References[edit]

- ↑ The Montgomery Advertiser, May 20, 1908. [1]

- ↑ Ordinance No. 7, Series No. 19, City of Pensacola. August 5, 1929.

- ↑ Ordinance No. 10, Series No. 1, City of Pensacola. November 30, 1931.

- ↑ Contract between Gulf Power and the City of Pensacola dated December 31, 1931.

- ↑ MyFlorida.com

- ↑ Google Maps Street View

- ↑ Google Maps Street View

- ↑ Ortiz, Paul. Emancipation Betrayed. University of California Press, 2005.

- ↑ "Jim Crow Law Effective To-Day." Pensacola Journal, October 13, 1905.