Segregation

Segregation was the institutional subjugation of blacks following the Civil War and subsequent passage of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments that constitutionally abolished slavery and secured the rights of former slaves. Like other areas in the South, Pensacola was engaged in policies of legal segregation through Jim Crow laws and other means.

Background[edit]

The origins of institutionalized segregation may be traced to the contentious 1876 election of president Rutherford B. Hayes, who ordered the withdrawal of federal troops from the South, effectively ending the Reconstruction period.

Pensacola played a pivotal role in the so-called Compromise of 1877 that delivered Florida's electoral votes (and thereby the election) to Hayes. One of the Florida's electors for Hayes, Pensacolian Frederick C. Humphreys, faced objections by the Democrats that he was constitutionally ineligible to cast a vote because he also held a federal office as shipping commissioner of the Port of Pensacola. Humphreys was able to provide proof that he had resigned from the shipping position a month before the election, and with the matter resolved, "it was such as to give all but absolute assurance that the next President will be Rutherford B. Hayes."[1]

Reconstruction was seen by many white Southerners as an affront to their regional sovereignty, an attitude that would endure for decades; William Tyler, Superintendent of Public Instruction in 1930, wrote praising "the overthrow of the carpetbag governments … after which the South was permitted to continue its own reconstruction policies."[2]

Prior to the end of Reconstruction and shortly thereafter, African-Americans had enjoyed relative success in Pensacola. Individuals of color, like Salvador Pons and Zebulon Elijah, had been elected to public office.

Streetcar segregation[edit]

In 1905, John Campbell Avery, Jr., State Representative for Pensacola, introduced a bill providing for the segregation of streetcars. The summary of the bill was as follows:

An act to require street car companies and others in this state, to furnish separate cars or divisions for white and colored passengers; to require said companies and others to keep white and colored passengers in their respective cars or divisions; to give conductors and employees of said companies police powers; and to provide penalties [$25 fine and/or 30 days' imprisonment] for the violation of this act.[3]

Pensacola's black population responded immediately to the bill (which the legislature would pass both houses unanimously on May 12) by boycotting the streetcar system. A report was sent to streetcar parent company Stone & Webster saying, "In Pensacola 90% of the negroes have stopped riding even though the company has not issued an order or intimated anything as to what they intend to do. The negroes have appointed Committees who meet negroes visiting their city at the train and present each one with a button to be worn in the lapel of the coat. This button bears the single word WALK."[4] Some African-Americans rode the streetcars despite the boycott, but according to the Pensacola Journal, "in each case when they are seen by persons of their own race they are subjected to taunts and cries of 'Jim Crow.'"[4]

The law went into effect on July 1, 1905, the full text of which read:

A bill to be entitled an act to require street car companies and others in this state, to furnish separate cars or divisions for white and colored passengers, to require said companies and others to keep white and colored passengers in their respective cars or divisions, to give conductors and employees of said companies police powers, and to provide penalties for the violation of this Act.

Be it enacted by the legislature of the State of Florida:

Section 1. That all street car companies, persons, associations of persons, firms or corporations operating street car lines in this State shall furnish separate accommodations for white and colored passengers.

Sec. 2. That every street car company or person operating a street car line in this state shall make provision, rules and regulations for the separation of white passengers from negro passengers by separate cars, or fixed divisios, or movable screens, or other method of division in the cars of such lines. A failure or refusal by such company or person to make such provision, rules and regulations shall be a misdemeanor, and upon conviction thereof it or he shall be punished by a fine not to exceed fifty ($50.00) dollars for each offense. Each day of such failure or refusal after July 1, 1905, shall constitute a separate offense.

Sec. 3. That when any street car is divided into divisions, the divisions set apart or provided for white and colored passengers, respectively, may be in space proportioned according to usual and ordinary volume of travel by white and colored passengers on the line on which the car is used.

Sec. 4. That conductors or other employes in charge of such cars shall assign passengers to their respective car or division, provided by said companies under the provision of this act, and such persons in charge of such cars are hereby invested with police powers to carry the provisions of this act into effect.

Sec. 5. That any passenger willfully occupying any car or division of car other than that to which he has been assigned, shall be guilty of a misdemeanor, and be punished by a fine not to exceed $25.00, or by imprisonment not to exceed thirty days. Conductors and all other employes in charge of such cars or divisions of cars are hereby clothed with the power to eject from the car or cars any passenger who refuses to occupy such car or division to which he may be assigned.

Sec. 6. If any such employe having charge of any such car shall permit white and colored passengers to occupy the same car or division, he shall be guilty of a misdemeanor and punishable by a fine of not exceeding fifty dollars or imprisonment for not exceeding thirty days or both in the discretion of the court.

Sec. 7. That the provisions of this act shall not apply to colored nurses having the care of white children or sick persons.

Sec. 8. That nothing in this act shall be construed to prevent the running of extra, or special cars for the exclusive accommodation of either white or colored passengers, if the regular cars are operated as usual, as required by this act.

Sec. 9. That all laws or parts of laws in conflict with this act are hereby repealed.

Sec. 10. That this act shall take effect on the 1st day of July, 1905.[5]

The Pensacola Journal wrote after the law went into effect, "there is but little patronage from the colored citizens at present, but the increase in white traffic has made up for this, and the street cars are well patronized as before the boycott of colored residents was begun."[6]

In Jacksonville, an African-American minister named Andrew Patterson was arrested for violating the law, and his resulting lawsuit, Patterson v. Florida, contested the legality of segregation. On July 29, less than a month after the Jim Crow law went into effect, the Florida Supreme Court found for the plaintiff and struck down the law as unconstitutional — not in opposition of segregation per se, but because Section 7 of the act allowed "colored nurses having the care of white children or sick persons" to accompany their charges in the white section, "thus discriminating between the races" in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.[7] Thereafter, the Pensacola Journal noted, "The negroes began to ride early and it was noticeable that they almost invariably occupied the front seats."[4]

However, segregation was soon reinstituted when the City of Pensacola passed an ordinance (sponsored by the Chamber of Commerce) using modified Avery language. The ordinance was vetoed by Mayor Charles H. Bliss, out of concerns that it would also be found unconstitutional, but was passed by the council regardless. It went into effect on October 13, 1905.

L. B. Croom was jailed for violating the streetcar laws, and in the 1906 cases Croom v. Schad and Patterson v. Taylor these new segregation laws were upheld as constitutional.[8]

Desegregation[edit]

Desegregation of facilities occurred gradually over many years.

- Following a seven-month boycott led by the Pensacola Council of Ministers, lunch counters at all Pensacola businesses were integrated in early 1962.[9]

- August 27, 1962 – Twenty-one black students begin classes at nine previously all-white schools in the Escambia County School District. A bomb threat was called in to Pensacola High School, which received the highest number of black students, but was quickly determined to be a hoax.

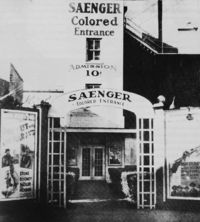

Images[edit]

1909 ad in The Pensacolian for Puritan Laundry, touting itself as "the first and only Laundry in the City for White People Only."

References[edit]

- Jump up ↑ "The Electoral Tribunal." New York Times, February 8, 1877.

- Jump up ↑ H. Clay Armstrong, editor. History of Escambia County. St. Augstine: The Record Company, 1930.

- Jump up ↑ "Mr. Avery's Race Separation Bill." Pensacola Journal, April 25, 1905.

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 4.2 Paul Ortiz. Emancipation Betrayed: The Hidden History of Black Organizing and White Violence in Florida from Reconstruction to the Bloody Election of 1920. University of California Press, 2005.

- Jump up ↑ "'Jim Crow' Law Is Now Effective." Pensacola Journal, July 1, 1905.

- Jump up ↑ "Jim Crow Law Now In Effect." Pensacola Journal, July 2, 1905.

- Jump up ↑ "Florida 'Jim Crow' Law Void." New York Times, July 30, 1905.

- Jump up ↑ Shira Levine. "'To Maintain Our Self-Respect': The Jacksonville Challenge to Segregated Street Cars and the Meaning of Equality, 1900-1906."

- Jump up ↑ Jet, March 15, 1962.