Pensacola streetcar system

The Pensacola streetcar (trolley) system was a public transportation system that was operated by various entities between 1884 and 1932.

This could not psobsily have been more helpful!

Contents

Demise of the streetcar system

In 1928 the St. Louis-San Francisco Railway bought the old dummy line for freight purposes; a bit of trackage still exists on the south side of Main Street between Clubbs and A, where the line curved southwest toward Pine.

In 1929, the City passed an ordinance authorizing Gulf Power to discontinue service and remove trackage for the portion of the system servicing the Hawkshaw area.[1]

The City authorized Gulf Power to surrender its streetcar franchise in November 1931, "in consideration" of an $18,000 credit to be applied towards the City's debt to Gulf Power.[2] After adoption of the ordinance terminating the franchise, Gulf Power agreed to reduce the interest rate on the City's debt from eight to six percent per year.[3] Streetcar service was discontinued in 1932, replaced by motor bus service operated by the Pensacola Coach Corporation.

At its peak, a total of 30 trolley cars carried four million passengers per year (1920).[4] Partially covered tracks and barely concealed right-of way are clearly visible in various places along the former routes, including on West Gadsden Street, West DeSoto Street,[5] and East Jackson Street.[6]

Segregation

Segregation of the streetcar system came in 1905 via a state law authored by Pensacola representative John Campbell Avery. Soon after the law was approved by the Florida Legislature, Pensacola's African-American community initiated a boycott of the streetcar system. The streetcar system's management reported on the boycott to the Stone & Webster corporate office:

| In Pensacola 90% of the negroes have stopped riding even though the company has not issued an order or intimated anything as to what they intend to do. The negroes have appointed Committees who meet negroes visiting their city at the train and present each one with a button to be worn in the lapel of the coat. This button bears the single word WALK. | ||

—Letter of John E. Hartridge to William H. Tucker, May 28, 1905.[7] | ||

However, the Avery law was declared unconstitutional by the Florida Supreme Court a month later. The Pensacola City Council responded with an ordinance that was

somewhat similar to the state law which was declared unconstitutional. It was drawn however, in such shape that it will hardly be declared unconstitutional if any attempt is made to carry it to the Supreme Court. The street railway company will divide the cars as it did during the time that the state law was being complied with, except that cards will be posted designaling the white and colored parts of a car. The colored population seems to be satisfied and it is not expected that the cars will be boycotted as was the case when the state law [became] operative.[8]

Despite being vetoed by Mayor Charles H. Bliss, the ordinance was passed by the council and went into effect on October 13, 1905.

Streetcar lines

East Hill Line

The East Hill line ran in somewhat of a loop, going up Alcaniz Street from Gregory to Brainerd Streets, then east on Brainerd to 6th Avenue, north on 6th Avenue to Blount Street, east on Blount to 16th Avenue, south on 16th to Jackson Street, then west on Jackson to 8th Avenue, then south on 8th to Wright Street.

North Hill Line

Belt Line

West Hill (or Park) Line

The West Hill or Park Link headed west on la Rua Street from de Villiers Street, turning north on J Street and terminating at Kupfrian's Park.

Other images

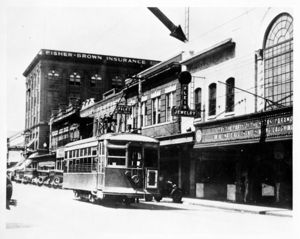

South Palafox Street, early 1900s

Bayshore line car, circa 1930

South Palafox Street near Plaza Ferdinand VII

The streetcar barn, 1908

References

- ↑ Ordinance No. 7, Series No. 19, City of Pensacola. August 5, 1929.

- ↑ Ordinance No. 10, Series No. 1, City of Pensacola. November 30, 1931.

- ↑ Contract between Gulf Power and the City of Pensacola dated December 31, 1931.

- ↑ MyFlorida.com

- ↑ Google Maps Street View

- ↑ Google Maps Street View

- ↑ Ortiz, Paul. Emancipation Betrayed. University of California Press, 2005.

- ↑ "Jim Crow Law Effective To-Day." Pensacola Journal, October 13, 1905.