Difference between revisions of "James C. Van Pelt"

(infoboxd!) |

(source: 2/4/1910 PEN) |

||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

| spouse = | | spouse = | ||

| parents = | | parents = | ||

| − | | children = | + | | children =Margaret Caroline |

}} | }} | ||

'''James Cornelius Van Pelt''' ([[February 8]], [[1864]] - [[July 31]], [[1927]]) served two terms as [[Escambia County Sheriff]], [[1903]]-[[1913]], and [[1917]]-[[1919]]. | '''James Cornelius Van Pelt''' ([[February 8]], [[1864]] - [[July 31]], [[1927]]) served two terms as [[Escambia County Sheriff]], [[1903]]-[[1913]], and [[1917]]-[[1919]]. | ||

Revision as of 18:57, 12 March 2008

| James Cornelius Van Pelt | |

|---|---|

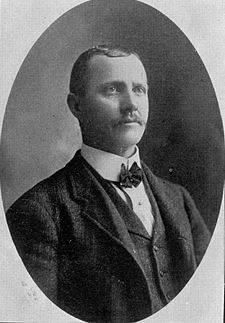

| From The Bliss Magazine, March 1904

| |

| Born | February 8, 1864 |

| Died | July 31, 1927 |

| Occupation | Farmer, Escambia County Sheriff |

| Children | Margaret Caroline |

James Cornelius Van Pelt (February 8, 1864 - July 31, 1927) served two terms as Escambia County Sheriff, 1903-1913, and 1917-1919.

Van Pelt was a farmer, dairyman and merchant by trade. He was named sheriff in 1903 after the unexpected death of George E. Smith. He presided over a eventful and tumultuous period in the history of Escambia County, Florida, from massive construction projects that transformed downtown Pensacola to events like the Pensacola Streetcar Company strike of 1908. In 1912, Van Pelt oversaw the completion of the Court of Record Building and transferred prisoners to the new jail contained therein. Van Pelt was defeated in the 1912 election by A. Cary Ellis, but ran again in 1916 and won.

In 1919, Sheriff Van Pelt was involved in a scandal involving liquor distillation. The Eighteenth Amendment had been ratified at the time, but it would not go into effect until January 16, 1920. Nevertheless, due largely to the administration of Governor Sidney J. Catts, a member of the Prohibition Party, Van Pelt was removed from office.

Leander Shaw Incident

On July 29, 1908, Sheriff Van Pelt was warned of an angry mob determined to lynch Leander Shaw, a black man accused of raping a white woman, Lillie Davis. The sheriff and several deputies gathered on the steps of the County Jail, where Shaw was being held, and several other prisoners were transferred to the jail's backyard for safety. Van Pelt reportedly deputized the entire crowd, apparently thinking that the mob would have to obey the law and disperse if its members were sheriff's deputies. The tactic failed; instead the members of the crowd yelled, ""If we're deputies, open the gate and let us in!"[1] According to the Pensacola News, "a mob variously estimated from 1000 to 1200 stormed the jail," at which point Van Pelt blocked their entry with an ultimatum:

| Gentlemen, here I am. You can kill me if you want to, but if you get my prisoner, it will be over my dead body. I have sworn to do my duty, and I am going to do it if I die for it![2] |

The sheriff was seized by several men and wrestled to the ground, at which point his gun discharged, killing a member of the crowd and further agitating the mob. Sheriff Van Pelt and his brother, John A. Van Pelt, were injured in the resulting melee, and Shaw was taken and hanged from an electric pole in nearby Plaza Ferdinand VII.

The documentary film Lillie & Leander: A Legacy of Violence depicts this incident and its aftermath.

References

- ↑ "Lillie & Leander: A Legacy of Violence." Independent News. April 19, 2007.

- ↑ John Appleyard. The Peacekeepers: the Story of Escambia County, Florida's 43 Sheriffs. 2007.

| Preceded by: George E. Smith |

Escambia County Sheriff 1903-1913 |

Succeeded by: A. Cary Ellis |

| Preceded by: A. Cary Ellis |

Escambia County Sheriff 1917-1919 |

Succeeded by: Curtis S. Whitaker |