Streetcar operators' strike

A strike was staged by the operators of Pensacola's electric streetcar system from April 5–May 13, 1908. The workers struck as a result of disputes with their employer, the Pensacola Electric Company. The 39-day strike, which drew attention from national labor leaders and was reported on in the New York Times, resulted in open violence on Pensacola's streets and the declaration of martial law. At the conclusion of the strike, at least one individual had died (with many more injured), and the Pensacola Electric Company had suffered significant financial losses, though the company did manage to break the strike.

Contents

Origins of the strike[edit]

In 1906, Pensacola's streetcar system was purchased by the Boston-based firm Stone and Webster, ending local ownership of the system. Stone and Webster incorporated the Pensacola Electric Company and administered the company through a local manager. In January 1908, the system's motormen and conductors had organized and formed a union, affiliated with the Amalgamated Association of Street Electric Railway Employees of America (now the Amalgamated Transit Union). Over the next several months, various issues, including pay and company rules and practices, were disputed. At the center of the dispute was a company rule which required workers whom the company had suspended for whatever reason to report to the company's car barn thrice daily for a roll call. The workers contended that the rule was “unjust” and that it would “deprive [suspended workers] of the opportunity of doing other work while under suspension”. The company held, however, that the rule was instead a “very necessary discipline for [workers] who have been in the habit of purposefully and willfully violating some rule of the company in order to secure a holiday which otherwise would not have been granted them”.

On Saturday, April 4, the union's president, G. C. McCain, was fired by the company. The next evening, the workers voted to strike. While the union maintained that the strike was the result of unresolved disputed over key issues including the roll call rule, the company, through its local manager, John W. Leadley, contended that the dispute and the strike were engineered solely by McCain and those sympathetic to him, and that no real dispute existed. Furthermore, the company refused to recognize the workers' union.[1]

According to the union, the mayor was notified of the impending strike at 6:40 pm, and was furthermore asked to notify the company, although he was unable to do so until the following day. The union officially declared the strike at 7:10 pm. Shortly thereafter, the striking motormen and conductors started bringing streetcars into the the barn, disrupting service across all lines except the Bayshore line. The cars on the Bayshore line were operated by agents of the company and continued to run until midnight.

Initial stages[edit]

The next day, Monday, April 6, McCain and the striking workers stopped and boarded a Bayshore car returning to Pensacola from Fort Barrancas. The company agents operating the car surrended control to the strikers without violence. The strikers then returned the car back to Pensacola, let off its passengers, and took the car into the barn, disrupting service for the remainder of the day.[2] Pensacola mayor C. C. Goodman, though he had initially tried to arbitrate the dispute, ultimately took the position that, as head of the City government, his utmost obligation was to ensure the Pensacola Electric Company met the demands of its franchise agreement with the City of Pensacola to furnish reliable streetcar service, even if that meant running the lines with strikebreakers. Goodman sent the following dispatch to the offices of the Pensacola Electric Company:

| Gentleman: I notice that your cars are not being operated this morning on all lines of the city. As mayor of Pensacola, I hereby demand that you shall renew and continue the operation of your cars in accordance with the provisions of your franchise ordinance. Let me have your answer in regard to this matter today. | ||

—“Pensacola Electric Company and Its Employees Lock Horns,” Pensacola Journal, April 7, 1908. | ||

The union viewed Goodman’s actions as hastening the company’s use of strikebreakers, and Goodman was regularly disparaged in the union’s strike bulletins.[3]

Strikebreakers arrive[edit]

At the onset of the strike, the Pensacola Electric Company had begun placing ads for local strikebreakers, but only one man responded. Thereafter the company sought to import strikebreakers from out of town in order to resume service. The strikebreakers, brought into the city by the Pensacola Electric Company from New York and elsewhere, began arriving in Pensacola on April 10 and continued to come into the city for the next several days.[4] The company erected housing for the men in the car barn. After a mob of strikers and sympathizers met the first train strikebreakers violently, Florida Governor Napoleon B. Broward ordered the state militia into Pensacola. Companies K and M of the state militia arrived on the evening of April 11. After their arrival the militia provided security for the strikebreakers, meeting them upon their arrival and escorting them to the company’s car barn.[5] The state troops were quartered at the Old Escambia County Courthouse and in tents in the median of North Palafox Street.

On April 10, Mayor Goodman ordered all saloons closed until further notice, and the next day issued an order imposing a 10:00 pm curfew and prohibiting until further notice all public gatherings other than sessions of schools and churches.[6] On the afternoon of April 14, the company resumed limited service on two lines,[7] with the cars being operated by strikebreakers, and the lines being guarded by more than five hundred state militia troops.[8]

As the lines continued to be run by strikebreakers, Florida Adjutant General Clifford Foster, Escambia County Solicitor Scott M. Loftin, and other parties worked to bring the two sides together to mediate the dispute. Progress seemed to be made (Foster stated on April 15 that the prospects of a settlement were “very bright”),[9] and as a result, strike-related tension and violence tapered off, and state militia troops began to withdraw from the city, with only one reserve company remaining in the city by April 20.

However, on April 21, a crowd fired upon a streetcar on the West Hill line and fatally wounded the conductor, a Mr. G. Hoffman.[10] Mayor C. C. Goodman offered a $250 reward "for the apprehension and conviction of the paarty or parties who did the shooting."[11] Two strikers were arrested in connection with the shooting, and, although the men were later released, the previously widespread support of the public at this point began to diminish. Stenographer W. L. Wittich, Jr. was also fired upon while boarding a streetcar.

On the evening of May 11, a streetcar was dynamited on the East Hill line. Although there were no passengers on board, and the two operators were uninjured, and there was only minimal damage to the car, the act was vilified in the press. The Pensacola Journal called the act "dastardly". The union promptly denounced the act and denied that any of its members were responsible. A Union Bulletin of May 12 noted, “It is to be regretted because whether or not a union man did the work, the company will so charge, and at least a portion of the public so believe.” On May 13, the City Council authorized a $500 reward for an arrest in the case.[12]

The strike is broken[edit]

Despite much support from the community, the strike was eventually broken. While initially no strikebreaker-run cars were operated after 6:00 PM, by April 25 the Pensacola Electric Company was able to operate all lines on the regular full schedule. As a show of solidarity with the union men, employees at the Pensacola Navy Yard had begun using chartered boats for their commute, refusing to patronize the streetcar lines run by strikebreakers. However, this practice was stopped when the Yard’s commandant issued an order prohibiting the vessels from landing, forcing the Yard workers to use the strikebreaker-run Bayshore line to get to and from work.[13] This, combined with the turning public opinion, and the adamant refusal of the company to negotiate or submit to arbitration, did much to hasten the end of the strike.

Their spirits broken by a month of unemployment, on May 11, sixteen of the striking workers begged Manager Leadley for their jobs back, although they had won no concessions from the company.[14] As a condition of their reemployment, the men had to sign the following statement, which was thereafter published in the Pensacola Journal:

| We, the undersigned, who have been heretofore employees of the Pensacola Electric Company, and among those who went out on a strike on April 5, 1908, have again accepted employment with that Company, have ceased to belong to Division 234 of the Amalgamated Association of Street and Electric Railway Employees of America, and have signed a contract with the Electric Company, that should we Join a union hereafter, our connection as employees with that Company shall cease, and we desire to state to the public, through you, our reason for our action. We are satisfied that the strike into which we entered was not justified by the circumstances existing at the time, and that it was unauthorized by the constitution of the Association itself. We believe that a further continuance of the strike would not only be a wrong to the public, but would deprive many of us and our families of the means of subsistence, and we cannot think that it is right for us to continue the wrong which we have begun. For these reasons, we have taken the course which we have stated, and believe that the public will appreciate that our position this time is right. | ||

—“Sixteen Conductors and Motormen Return to Work,” Pensacola Journal, May 12, 1908.[15] | ||

On May 13, after another streetcar was nearly but unsuccessfully dynamited, the remaining unionized strikers officially ended the strike, but were not offered back their jobs.[16]

Impact of the strike[edit]

The strike ended without a clear victory for any side. The public was perhaps the biggest loser; at least one person lost their life as a result of strike-related violence, and many more were injured. The taxpayer dollars spent by government in response to the strike, such as to finance the state militia troops that entered the town, cannot be estimated. While the company did manage to weather the strike without making any concessions to the union, and indeed they were able to fracture the union to some degree, the cost to the company in lost revenue and the importation of and room and board for strikebreakers was significant.

The strike, although unsuccessful, prompted labor unions to politically organize their membership to an unprecedented degree. Nearly all of the local candidates endorsed by labor unions scored large victories in the May elections.

Community support[edit]

For the duration of the strike, the striking workers received plentiful support from the community. Donations to the striking men from the community totaled at least $500. Numerous businesses, including the West Florida Steam Bakery and Paragon Meat Market, offered the strikers and their families food, goods, and services free of charge. The Crescent Theatre held several benefit matinees of which proceeds went to the striking men. Many sympathizers showed up to union meetings and wrote letters to editors of local newspapers. Editorially, the local newspapers remained for the most part neutral, taking the side of the public interest, and urging both parties to meet and arbitrate their differences.

On April 11, a crowd of men and boys estimated to number between 200 and 300 followed and harassed Manager Leadley to the point that city police were required to disperse the crowd and escort Leadley to his office.[17] Young boys were reported to throw stones at strikebreaker-run streetcars.[18] On April 24, twenty-four City of Pensacola police officers – two thirds of the entire force – refused to board and protect streetcars which were being operated by strikebreakers.[19] They were suspended and later fired.

Other images[edit]

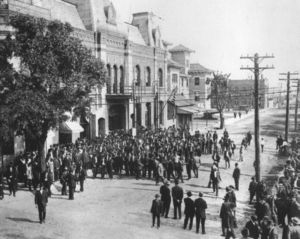

The striking employees of the Pensacola Electric Company

State militia outside the Old Escambia County Courthouse

State militia posing on the steps of the Federal Customs House & Post Office

Strikers in tents advertising strike rally at Opera House

References[edit]

- Jump up ↑ “Street Railway Employees of Pensacola Go Out on Strike, Tying Up the City Lines,” Pensacola Evening News, April 6, 1908 (Special Morning “Extra” Edition)

- Jump up ↑ “Strikers Capture Street Car This Morning Without Bloodshed,” Pensacola Evening News, April 6, 1908.

- Jump up ↑ “Dope About Town,” Union Bulletin (Pensacola,) May 12, 1908.

- Jump up ↑ Wayne Flynt. “Pensacola Labor Problems and Political Radicalism,” The Florida Historical Quarterly 43, no. 4 (April 1965): 319.

- Jump up ↑ “43 Strike Breakers Arrive in Pensacola,” Pensacola Journal, April 11, 1908.

- Jump up ↑ “State Troops Arrive; More Are Expected,” Pensacola Journal, April 12, 1908.

- Jump up ↑ “Cars Are Operated Guarded By Troops,” Pensacola Journal, April 15, 1908.

- Jump up ↑ Flynt, 323.

- Jump up ↑ “The Prospects of a Settlement of the Strike Very Bright,” Pensacola Journal, April 15, 1908.

- Jump up ↑ Flynt, 323.

- Jump up ↑ Minutes of Pensacola City Council, April 22, 1908.

- Jump up ↑ Minutes of the Pensacola City Council, May 13, 1908.

- Jump up ↑ “Strikers Call Off Street Car Strike,” Pensacola Journal, May 17, 1908.

- Jump up ↑ Flynt, 325.

- Jump up ↑ “Sixteen Conductors and Motormen Return to Work,” Pensacola Journal, May 12, 1908.

- Jump up ↑ Scott Satterwhite, “The Great Pensacola Streetcar Strike of 1908,” Boogie Pensacola, February 23, 2000.

- Jump up ↑ “Leadley Followed By 300 Men and Boys on Palafox,” Pensacola Journal, April 12, 1908.

- Jump up ↑ “Settlement Fails, More Men Expected,” Pensacola Journal, April 17, 1908.

- Jump up ↑ “Twenty-Four Policeman Refuse to Obey Orders,” Pensacola Journal, April 25, 1908.